When I look at the empty stage before a concert, I often wonder how many people in the audience realise they are about to witness a form of violent entertainment? The thought disappears, drowned beneath the sounds of the orchestra tuning, the notes, the enjoyment, but even as I forget it, I know there will come a time when the thought will return.

I can’t remember when this notion first occurred to me. Perhaps it was in the early 2010s, when I discovered the novels of Elfriede Jelinek and Thomas Bernhard, maybe a little earlier, but I certainly didn’t think this way in the spring of 2005 when I walked on stage to hand a conductor a bunch of flowers.

I was 16 and undertaking work experience at the music library of a large symphony orchestra. I was about to finish ninth grade. I had just auditioned for the Sibelius Academy youth department for the second time. That autumn I would start evening high school, so I would have more time to practice.

I was a few days into my two-week work experience. It had been fun. My colleagues in the orchestra office seemed to consider me their equal, and one day after rehearsals Alfred – a talented, charismatic orchestral player in his thirties – asked me if I’d like to go for a walk to the rocks behind the Helsinki City Theatre. I remember asking my school friends whether it was possible I was infatuated with a man almost twice my age.

Alfred played in the concert that evening; I walked on stage, the concert was over.

At some stage he caught up with me, or was I waiting for him? He asked me into one of the dressing rooms at Finlandia Hall, offered me alcohol, we kissed. Or did I go there of my own accord? In any case, he was the one who offered me the alcohol.

I think it was a gin long drink, but I can’t remember. It was fifteen years ago. My memories have congealed into a shapeless mass, the bright spots no longer in any semblance of a linear timeline.

I’m not sure when I heard that one of my colleagues sitting in the audience had noticed Alfred’s eyes following me as I walked on stage with the flowers. Neither am I sure whether there really was an eerie darkness when I arrived at the office the following day. Or how much of my work-experience contract was left when a pink flower appeared on my desk.

I don’t remember when someone told me that Alfred had placed a bet with another musician that he would have sex with me. And did Alfred send me messages the following summer and ask me to go abroad with him? I can’t be sure, but I have feeling he did.

A few years ago, my violinist father visited me at my then apartment, which was also his childhood home, looked at a pile of books on the floor and said something to effect of, are you really reading that shit?

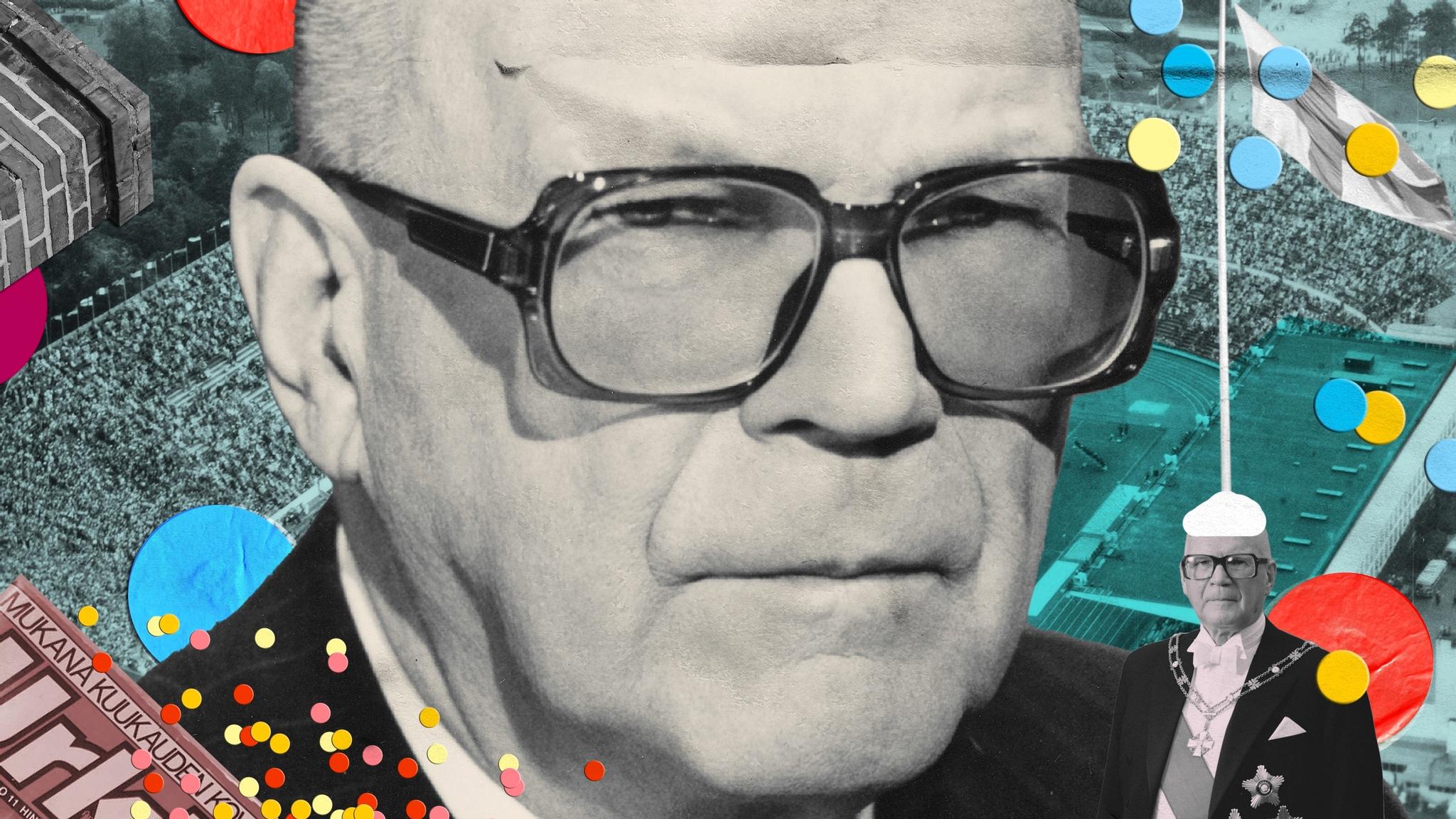

The book in question was music critic Seppo Heikinheimo’s memoir Mätämunan muistelmat (‘Recollections of a Rotten Egg’), a book that my father had no desire to open.

To quote an article about Seppo Heikinheimo, published in 1993 in the Finnish cultural magazine Image, For some things in this world, there is no explanation. And certain combinations of things are mutually incompatible. One such combination is artists and critics. They are two utterly different species: the two faces of Janus; Adam and Eve; crime and punishment; Jesus and Judas.

Perhaps my father considered my reading Heikinheimo’s book a form of patricide, one that I would continue a few years later when I started writing music reviews for Heikinheimo’s erstwhile employer the newspaper Helsingin Sanomat.

The 1993 article in Image claimed that Heikinheimo had succeeded in encouraging those who didn’t care for “works longer than three minutes” actually to read reviews of classical-music concerts. This he did, in part, by “calling a spade a spade”. With hindsight, his writings cannot be considered particularly prophetic; for instance, he once claimed that Kaija Saariaho, who in a 2019 survey conducted by BBC Music Magazine was voted the most important living composer in the world, writes bad music and that she only garners attention because of her ethereal appearance. Be that as it may, people didn’t read his columns so much for the wisdom of his proclamations but because he had become an acerbic institution in his own right, and one that it was exciting to observe from the outside.

In doing so, Heikinheimo succeeded in traumatising a generation of musicians and, perhaps in association with a number of his male colleagues, cast a shadow over the field of artistic criticism that has not yet fully lifted. I have often wondered whether he ever truly understood what he was doing to musicians. I have been planning to write about this subject for some time.

The banality of nastiness came to mind again in January while I was talking to a musician with a significant career and who is well acquainted with the Sibelius Academy. After considering the ways in which certain critics have abused and continue to abuse their power, I began to think about the accepted practices upon which the music world is constructed and eventually came to consider more broadly the relation between classical music and the #metoo movement.

I’ve seen it myself, witnessed the way relationships between teachers and students begin in a drunken haze at festivals and music camps. I know the people there are rumours about. I’ve been aware of some of these stories for so long that I didn’t even realise I knew about them. They are a part of my childhood memories that I simply take for granted.

The musician I interviewed told me about the harassment she experienced and that she witnessed herself as a student. There are countless examples. She told me she knew of at least five teachers still on the Academy payroll who had definitely had relationships with students. Of the names she mentioned, I had heard almost all of them before.

The conversation moved from sexual harassment to other (ab)uses of power during lessons. Humiliation, shaming, harsh criticism. This musician told me she too had been humiliated as a student.

“[For the humiliator] it’s terribly satisfying, empowering, talking to someone like that. You construct a force field around yourself, one based entirely on fantasy.”

The musician told me she has thought about the problematics of nastiness for years. She cannot think of a single situation in which it might be useful.

I too have thought about this and many other topics besides. I’ve wondered why classical musicians put such emphasis on the idea of tradition, whether critics and performers really need to position themselves on different sides of the fence, and whether this fence is something I’m only imagining. More than anything, I wonder why I didn’t write this article years ago.

In a strange way, it feels as though, one way or another, all these questions are about dichotomies, Jesus versus Judas, stones and glass houses, the experience of holiness, rituals and shapeless images.

It is about what #metoo really means.

My memories of Maaren: writing in a chunky diary in the school classroom that served as a bedroom at orchestra camp; going for a run; wearing a burgundy velvet skirt.

I first met Maaren at music camp in the early 2000s. She was a few years older than me, already studying at the Sibelius Academy youth department, talented, uncannily beautiful.

After camp, we kept in touch. Oftentimes we would meet up in a café somewhere in downtown Helsinki and have salad for lunch.

My life wasn’t very exciting. I remember feeling ashamed whenever Maaren asked about my ‘boyfriend situation’. I had nothing to tell her.

But Maaren had something to tell. She was head over heels about Ville, a teacher at the Sibelius Academy, married and several decades older than her. Maaren told me they’d had a fling.

If I remember correctly, I didn’t think there was anything particularly wrong with this. I might even have been a bit jealous. Teachers only fall in love with the prettiest, most talented students, I thought.

Maaren was a bit baffled by the situation, but she was used to the attentions of older men. On one occasion, at another music camp, a man twice her age had invited her up to his hotel room. When Maaren refused to have sex with him, claiming she already had a boyfriend, the man proceeded to masturbate in front of her. Maaren was fifteen at the time. She didn’t realise that this act probably constituted the sexual abuse of a child.

Maaren and Ville’s relationship began later that autumn after an innocent comment at an all-night post-concert after-party. Ville had clearly already had a few glasses of red wine and struck up conversation with “How’s it going?”, Maaren wrote in her diary. At the after party, Ville asked her to dance. That’s where it all started.

The relationship wasn’t a secret. Maaren and Ville hung out together in places where there were lots of other Sibelius Academy students. This is all in Maaren’s diary, as is the fact that to begin with she was hesitant and didn’t want anything to do with Ville. I don’t even fancy him, she wrote. Nonetheless, she experienced pangs of jealousy whenever it seemed as though Ville was showing attention to anyone else.

Ville called her at night, quite often when Maaren was at her parents’ house in another town. He praised her playing and wanted to see her.

The following summer, Maaren and Ville were at the same music festival together. By now she was very infatuated, maybe even in love, though she wrote in her diary that she doesn’t believe in love. I don’t believe in anything but music, she wrote. It was her religion. By that logic, Ville must some kind of god, she concluded.

Maaren listened to Ville’s recordings and wanted to spend more and more time with him. It was hard to concentrate on anything else. She realised she should take things easier, but it was hard.

I could put an ad in the paper asking for a saviour. I really need a saviour right now, a male one, she wrote.

Rumours about Maaren and Ville’s relationship began to spread. Eventually it became part of the collective history of a particular generation of Sibelius Academy students. At least one other member of staff knew about it while it was still going on. For a long time, whenever one of Ville’s female students changed teacher, everyone suspected sexual harassment.

Once the relationship had been going on for about a year, Ville turned up at Maaren’s house and said they had to put an end to it. Maaren already suspected this might be on the cards, or so she wrote in her diary. She almost wept, thought “everything Ville said was smart and true”, and they should have called it a day “ages ago”.

Maaren tried to talk about other things. If only the relationship with Ville could become normal, stable, she wished in her diary.

We hugged, and then he left. I ran to my bed in tears. It felt as though a real relationship had come to an end, though Ville said this was all just a daydream.

Even after this, Ville continued to call her. Then Maaren began dating someone else. Once again, she had a reason to say no.

Equality in the classical-music world has been the subject of much debate all autumn. The debate began in earnest when music critic Wilhelm Kvist from Hufvudstadsbladet, Finland’s main Swedish-language newspaper, wrote about a survey revealing that, of all the music performed by Helsinki orchestras, only 4% was composed by women. Later, Helsingin Sanomat published its own article revealing that, nationwide, the percentage was even lower.

Follow-up articles began to appear. There has been talk of quotas and the relationship between quality and equality. Can the two even be separated?

There has been discussion of conductor Leif Segerstam and his habitual sexual innuendo. The entire Finnish music world knows about Segerstam and his comments. There are so many examples that listing them here seems like a waste of paper. In an interview in a Danish newspaper, Segerstam criticised conductor Susanna Mälkki because she “hasn’t got any balls”. I have heard stories of comments about people’s appearance, routine humiliation of musicians, and of one instance when, on the terrace outside St Urho’s Pub, a locale popular among musicians, Segerstam asked an orchestral player what colour “pussy hairs” she had.

‘Time to apologise for the sexism’ was the title of Kvist’s article of 16th December 2019.

Leif Segerstam apologised. Not unreservedly, but still.

Finally, we were having a conversation. We’ve talked about gender. We’ve talked about traditions. We’ve even talked a bit about sexual harassment. There’s been an admission that this is important.

Haven’t we talked enough already?

In November, I was a guest on Jälkinäytös, an early-morning cultural debate programme produced by YLE, the Finnish broadcasting company, on a panel that also included the choreographer Sonya Lindfors and the journalist Kalle Kinnunen. We talked about classical music. I said I thought it was a bit strange that #metoo hadn’t really had any impact in the classical-music world yet.

At 10.20 a.m. my Messenger pinged. It was a message from Riikka, someone I knew from the time when I used to play. We had done gigs together when I studied at the Sibelius Academy youth department and Riikka was at the University of Applied Sciences, but we hadn’t been in touch for over ten years.

“Hi, thanks for asking why there’s been no discussion of #metoo in the classical scene and putting the cat among the pigeons on TV this morning. You saved my day. Thanks!! <3”

A few years ago, a case was being put together. Two teachers at the Sibelius Academy seemed to have been sexually harassing students for years, and in the case of at least one of them, this was going on until very recently. The same teacher had harassed Riikka years ago, suggested they meet up, and sent her text messages full of innuendo. When Riikka didn’t show any interest, the teacher started humiliating her in front of the class, saying he was ashamed to have her as a student. That’s what Riikka told me.

A journalist had asked her about this event. But there as another event too, one with far greater significance for Riikka.

In the town where she grew up, there were three talented girls in her class: Riikka, Milla and Sanna. Was Riikka their teacher’s favourite? At least that’s what it looked like to Milla.

Their teacher gave Riikka lots of opportunities: orchestra gigs and longer instrumental lessons.

Riikka had started taking lessons with Markku in seventh grade. She’d had a difficult family background. She wasn’t in touch with her father, and gradually Markku became the most important adult in her life. If her lesson went well and Markku praised her, Riikka felt that she was a ‘good kid’ and that maybe there was something good about her after all.

Markku often berated her too, put her down with a single word, or compared her to others. But then he praised her again, gave her a longer lesson or arranged a gig with the orchestra. At those moments, Riikka felt that she must be good at something after all. Otherwise, why would Markku do those things?

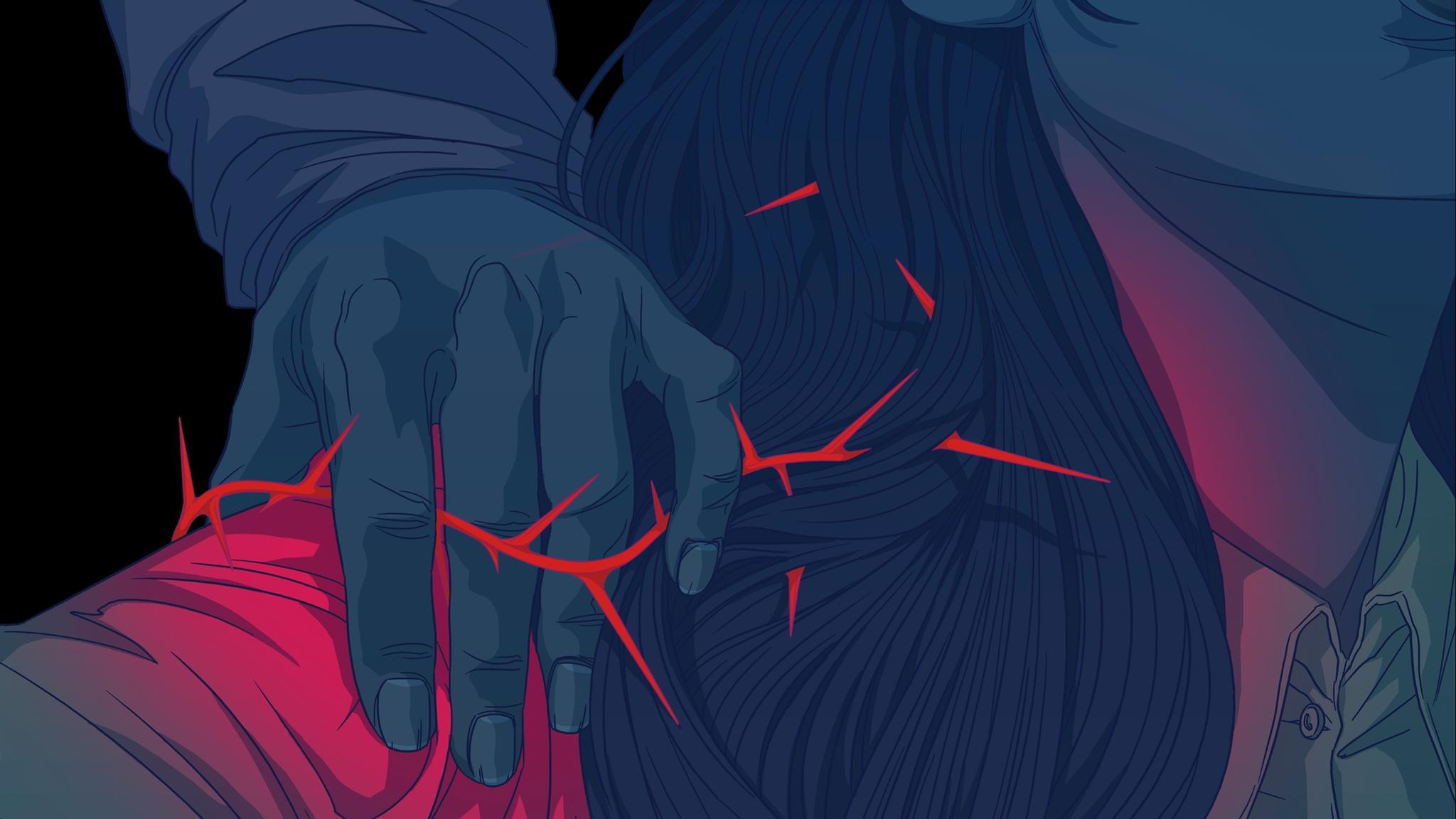

“I think it started in the last term of high school, at the party after the first night of a theatre project. I was just telling Markku that… I remember thinking, now’s the moment, I’ll tell him that he’s a real father figure for me. I was so childish and naïve that I thought, if I ever get married, I want him to give me away at the altar. I really thought of him as a father. Then I remember, I was about to open my mouth and say it, but I got the impression that he didn’t want me to say it, so he made the first move and told me he was in love with me or interested in me sexually. That was the start of months of sexual harassment, pushy, intrusive behaviour and attempted rape; by some standards it was probably rape.”

How could I have been so stupid that I actually thought I was talented, Riikka wondered years later.

The article for which Riikka was originally interviewed was never published. To date, the harassment and culture of humiliation within Finnish classical-music circles has yet to be afforded comprehensive public scrutiny.

I call round my musician friends and ask them why that is. Good question, many reply. Why?

A few matters that come to the fore.

The hierarchical culture. It’s hard to imagine an institution more hierarchical than the symphony orchestra. There are clearly defined roles, specific working hours, the expectation to play in a certain way, and the conductor, who in many orchestras is still addressed as maestro.

The genius myth. The idea that some individuals are exceptional is part and parcel of classical music, the idea that there have always been and always will be people who are naturally more gifted than others. There are a number of external structures that heighten this notion: for instance, works for soloist and orchestra. Soloists and conductors are the ones who receive attention in the press, whose performance is critically evaluated. In reviews, the orchestra is often presented as nothing more than a canvas that supports the soloist’s gestures and reacts to the genius of the conductor. In reality, the matter is never this simple. It is often the case that a conductor doesn’t do or give enough, and the orchestra survives by itself. If the concert goes well, such a matter goes unnoticed in the audience and the conductor gets all the credit. The conductor might have behaved badly too; there is a tendency to put up with behaviour like this.

Music as an apolitical entity. Music is viewed as a form of artistic expression that transcends dirty tricks and that doesn’t need to take a stance on worldly matters. Traditionally, ‘programmatic’ music, i.e. music with an extra-musical reference point, has been dismissed as amateurish and second-rate. Music should be absolute, it should be beyond such earthly concerns. You must be able to claim that only the music matters – not things like gender, age, ethnic background or which teachers you’ve had. Talent is everything. When you’ve been telling yourself this for long enough, such a ridiculous claim, debunked decades ago by social science, becomes a rational argument that can be used, for instance, to justify the fact that there hasn’t been a female cello teacher at the Sibelius Academy for decades.

Tradition. Classical music is founded on a canon that it is hard to question. It is another matter altogether whether the arguments advanced for why we play the same works by the same male composers are rational (no other high-quality music exists) or emotional (it just wouldn’t be Christmas without Beethoven’s Ninth), and how we should proceed. More to the point, are we imparting to future generations more than simply a musical canon? Are we imparting a culture of turning a blind eye? A culture of sexism, harassment and humiliation? That is, both mental and physical abuse? When we listen to classical music, what are we actually listening to?

The Master–Apprentice System. A music lesson is an exceptionally intimate situation, and the act of playing or singing is something so personal that a spectrum of emotions is bound to arise. Teachers’ teaching is not routinely monitored. Many students meet their teachers more often that they do their own parents. A teacher may become a parental figure of sorts – someone older, a role model, a trusted adult. It’s hard to report someone like that, even if they have done something wrong.

They say that music starts from silence.

I talk to almost a few dozen musicians, both men and women. Each of them has experience either of sexual harassment or humiliation, in most cases of both.

When she was 17, Eeva was playing a gig with Oulu Sinfonia when she was approached by Rami, an orchestral player about twenty years older than her. Rami told her she was a beautiful, talented musician and gave her some electric-blue nail varnish as a gift. Eeva wrote in her diary: Maybe it’s just because Rami is so sex-oriented, and that’s why he scares me. Pekka wasn’t like that. Rami has his moments too, when he was lying on top of me and looked at me with those sleepy eyes and said, “I think you’re so pretty right now”. But I don’t know, I don’t want to do anything that goes against my soul. It’s just so hard to tell him that sex is difficult for me, let’s just leave things as they are. Later on, when Eeva’s mother heard about it and got involved, Rami blamed Eeva and said she had come on to him.

When Ismo, who currently teaches at the Sibelius Academy, was studying abroad, he collaborated with a male accompanist in the habit of making insinuations with sexual undertones. Ismo pretended not to understand. Only later did he realise quite how much the continuous innuendo had disrupted his learning.

Emilia was sitting in an orchestra rehearsal when a male colleague started staring at her groin. Anything interesting down there? she asked him pointedly.

A female teacher told Amalia that she shouldn’t take lessons from other teachers. Whenever Amalia did have lessons with someone else, that teacher was belittled and scorned in class. You’re not thinking of changing teacher, are you? her regular teacher asked. Amalia remembers that whatever she said or did, the question was stupid. You have to “use your head”. Once she remembers trying something new. Are you an idiot? the teacher asked. It shows you in the music how to play it.

Milla’s task that week was to learn a scale. It didn’t feel difficult; nothing about playing her instrument felt particularly difficult back then. The scale went well in class. The teacher told Milla, that he couldn’t remember another student ever learning it this quickly. But don’t go getting any ideas, don’t imagine you’re better than anyone else, the teacher continued. The put-downs, the comparison and the humiliation continued until Milla eventually found a new teacher.

When Anu, who now teaches in many music schools, including the Sibelius Academy, was 16 years old, a teacher many decades her senior asked her to dance at a house party. They ended up in one of the bedrooms, lying on a bed and kissing.

At an after-party, a Sibelius Academy teacher took Sanni into another room, kissed her and suggested they have sex. At the time, Sanni was a student at the Sibelius Academy youth department. The other students saw what was going on, and Sanni didn’t end up in bed with the teacher. It was an uncomfortable situation for Sanni because she had been flirting with the teacher. As she puts it, she’d been learning to play the game.

Only recently, a female conductor was giving a guest performance with Alisa’s orchestra. Alisa’s colleague heard one of the players comment: “How can you concentrate on playing if you’ve got a constant hard-on?” Alisa wrote the comment down on her phone.

Other comments she overheard that week:

“This is what fucking happens when women stop concentrating on giving birth.”

“My beliefs forbid female priests – and conductors.”

Do you believe me yet? I could come up with another ten people who have had experiences like this. Probably more.

A was with a teacher who routinely humiliated students. So was B. C told me about her experiences of sexual harassment. I was standing right there when a teacher took D up to a hotel room. I might even have been a bit jealous!

And still I feel dirty, as if I’m doing something wrong by writing this down. I wonder about all the musicians reading this and thinking to themselves: is she really suggesting that listening to classical music is like watching a form of violent entertainment? Has she completely lost the plot?

I realise such a suggestion might be hurtful. I’ve spoken to many people for whom music is the most important thing in the world. It moves us, helps us, shapes our manner of being. Without music, I wouldn’t exist, many people think. And I certainly understand the sentiment, not through music but through other things. Alongside the monumental significance of music, our own ego and experiences, even unpleasant ones, become secondary when put into words.

I love music, and in many respects I have had a musical upbringing. And yet all this talk about the supremacy of music makes me think of a weird cult. It feels ludicrous to hear the things that people will justify in the name of music. Often, when the conversation turns to someone’s questionable pedagogical methods, we hear the clarification: yeah, but still, what a great musician.

Perhaps it’s for this reason that I have a sense of déjà vu reading Jelinek’s exaggerated and sadistic depictions of classical music or Bernhard’s The Loser, in which a pianist resorts to suicide because he isn’t as good as Glenn Gould. I love Bernhard’s Old Masters: A Comedy, too, in which the narrator derides all the great artists (I also enjoy Debussy’s Monsieur Croche – Antidilettante). In these works, it feels as though the bubble has been burst, the hierarchy is turned upside down and the ‘genius’ myth becomes a farce at which it is finally acceptable to laugh.

Moreover, these works remind us that, as wonderful as Beethoven’s symphonies are, we are allowed to have a variety of opinions about them. Further still, they remind us that no conductor or other genius has access to the thoughts of a dead composer. Nobody has the right to say, “this is how Beethoven wanted it”. To make such a claim is to play god without any right or justification. Tradition is just one story among many, and it isn’t always a very good story. This isn’t the best of all possible worlds!

Even ‘great’ artists are brought back to size. Like other mortals, they too are just people who, instead of operating in the humble service of music, lick the arses of the powers that be in order to make their own lot that bit better. The truth is shaped in relation to time: those who know the right people at a particular moment and speak their language garner the most attention. Nobody wants a revolution when they themselves are in power.

In writing this down, I am being honest. I have thought this in the past, and to an extent this is what I think now too.

What’s more, all the stories of harassment and humiliation that I have written about were told to me directly. I have no grounds to doubt their veracity or to imagine that these events didn’t happen in more or less the way they were described to me. In the majority of cases, I have heard about them not only from those involved but from other people too.

And still I am worried that I will unwittingly give a distorted impression of matters.

Over Christmas, I watched Whiplash, a film in which one of the main characters is a jazz teacher who employs sadistic pedagogical methods. After the film, my partner’s son and I debated whether the film told us anything about music. To my mind it did, to the boy (who plays the piano) it did not. At the time, we didn’t reach a consensus.

But I kept thinking about it. It was as though there was a level in the film that I couldn’t quite see.

It would be easier to resolve if we could identify the source of the wrongdoing, point our finger at a particular person. That has been the general trend in #metoo cases, the recent examples of James Levine, Plácido Domingo and countless others amply demonstrate. In identifying the ‘culprit’, the intent is to show that it is not our entire culture that is at fault but the unscrupulous behaviour of an individual or small circle. Even so, is this the whole truth?

In the Finnish classical-music scene, it is not only one individual who can be declared guilty of wrongdoing. Most of the incidents I have heard of were perpetrated by different people.

Having said that, from a certain perspective there are certain individuals whose behaviour is so egregious that we might consider it representative of this wider culture. It was for an article highlighting this that Riikka was interviewed, and though it was never published, the article could certainly still be completed. These people, who have behaved badly in the past, are current members of staff at the Sibelius Academy and other institutions, they are orchestral musicians and conductors. They are mostly men, because men have more power to abuse in the first place, but some are women – involved in sustained humiliation, sexual abuse and harassment.

But I’m not interested in finding the guilty party. I want to find solutions.

This paradigm is all around us. In Finland and abroad, in Helsinki and Turku, in Ostrobothnia, Lapland. It exists in a culture in which it is allowed to exist. At the time it happened, we didn’t even realise there was anything wrong with it – at least, I didn’t. Neither did Eeva, Maaren, Riikka, Anu, Ismo… That is why it’s taken me until now to write this article.

We only realised slowly, over time. And as time goes by, we realise all the more. Ultimately, we realise that something needs to change.

And to bring about such change, do we need a scapegoat that we can stone? Of all possible candidates, who might it be?

'I don’t know if you remember me. I’m Sonja Saarikoski. Ring any bells?’

‘Ummm…. Help me out a bit.’

‘I used to do work experience at the orchestra library. It was quite a while ago.’

‘Right, I remember! How are you doing?’

‘Well, fine, thanks. I’ve changed profession now.’

‘Okay.’

‘I don’t play any more. I’m in journalism these days. Actually, I’m writing an article, and that’s why I’d like to talk to you. Do you remember anything about what happened back then?’

‘Yes…’

‘What do you think about that now?’

‘I’m not sure, really. This is quite out of the blue. What is it you’ve got on your mind?’

I explain that actually I feel quite bad about it. After all, I was underage, I say. I heard that a group of friends in the pub had placed a bet that Alfred would sleep with me.

‘What? That’s absolutely not true. I didn’t say or hear anything about that. I can guarantee you, I’m not like that.’

‘Okay, then it’s really good that we’re talking about this now.’

‘Yes, it really is.’

‘But, you know a 16-year-old is still a minor, right?’

‘Yeah, but… I wasn’t much older… Well, it must have been 15 years ago, 20 years ago?’

‘I’m 31, so it was exactly fifteen years ago. If I remember right, you were almost 30.’

‘Surely not.’

‘You remember when you were born, right?’

At the time, Alfred was a few years younger than I am now.

‘I remember I really fancied you, and it was a hell of a long time ago. But if you want, I’ll be visiting Finland soon, we could meet up and talk about it in peace and quiet if you want.’

The article is urgent, I tell him.

‘Let me just ask you before you go: do you realise that if I was born in June instead of January, what happened would have been a criminal offence?’

‘Aha. But what… we didn’t even do anything.’

‘Well, we kissed in the green room at Finlandia Hall after we’d both been drinking.’

‘Right, yes. We kissed. But we didn’t do anything else.’

‘No, we didn’t do anything else.’

Much later on, I found out that it might have been a criminal offence after all. Though I was sixteen at the time – too old for what happened to be considered the sexual abuse of a child – according to Minna Kimpimäki, professor of criminal law of the University of Lapland, the act might have met the criteria of sexual abuse because I was still a minor and because the incident happened in the workplace.

Of course, you can never tell. A court of law determines whether a crime has occurred or not. It’s not up to me to decide, though I admit that during the agitated telephone exchange I suggested as much.

Now any hypothetical crime has expired in legal terms. Good. What happened is behind me; it doesn’t affect my day-to-day life.

Still, there are times when wrongdoing, especially that of a sexual nature, leaves us feeling embittered. If you find yourself wronged often enough or in a particularly grievous manner, you begin to wish that the wrongdoer will ‘get what’s coming to them’. You read Hélène Cixous, Rebecca Solnit, Kaari Utrio, depictions of thousands of years of the history of women’s subjugation and a culture of silence, and silently you shout: Exactly! I recognise this! I believe this is true!

The only problem with ‘an eye for an eye’ is that things don’t work like that. I don’t believe in ‘cancel culture’. We can’t suddenly refuse to engage with anyone who has done anything wrong at any point in their lives. Where would we even draw the line? This will only lead to blindness, the kind portrayed in films like Marriage Story and Kramer vs. Kramer.

In these films, couples who once loved each other end up in a prolonged custody battle, during which their respective lawyers dig up facts that, when presented in a certain light, make their former spouses look like monsters. All sense of perspective disappears.

I wonder whether #metoo runs the same risk. If matters are stripped of their background and context, we can easily forget that, until very recently, loose relationships between students and teachers were so normal in musical circles that at the time the victims didn’t realise they were being mistreated, abused.

Those guilty of humiliation and harassment must have learned these behaviours somewhere. They too may have been humiliated, shamed and criticised in the past. Perhaps they have been led to believe that this is the only possible path. Perhaps they have been on the receiving end of a damning review by Seppo Heikinheimo or some other critic, then gone on to read an article extolling Heikinheimo’s virtues.

Somehow they have ended up with the impression that the antidote to bad self-esteem is picking up a young woman.

Either that, or they refuse to change, because our ever-changing world frightens them. Tradition is good, rituals are important, and Mozart is beautiful, let’s not rock the boat! Maybe they are afraid that by admitting past misdemeanours they will make themselves useless, that in a society that is equal they will no longer be needed. This, too, is an understandable reaction.

That does not mean that these acts were right or justified. But I believe it means that, first and foremost, our manner of dealing with these acts must be something more constructive than simply punishing individuals. (Crimes that have not passed the statute of limitations are another matter.) It is the same logic whereby laws passed today cannot be applied retroactively.

This approach protects all of us from blindness or from taking the law into our own hands.

#metoo isn’t a simple thing. Based on the conversations I’ve had with many musicians, it is clear that there are at least two types of troublemaker. A member of the Sibelius Academy staff divided them into the ‘clueless’ and the ‘predators’. Predators are systematic in their behaviour and, as such, are clearly unsuited to working in pedagogical or managerial positions. It is the collective responsibility of schools, orchestras and anyone who witnesses this kind of behaviour to ensure that such people are removed from teaching positions and other roles in which they can exert power over others.

The majority, however, are those who have done something wrong and understand that they have done something wrong. It’s easy to do something wrong, as easy as, say, writing a blinkered, mean-spirited concert review. The logic is the same too: seeing the world in simple terms instead of complicated ones.

The same applies to sexual harassment and humiliation.

I believe this is exactly the case in most instances of wrongdoing – that people simply don’t understand the ramifications of their actions or their own motivations broadly enough to be able to act correctly. It demonstrates a lack of awareness and a paucity of thought; it makes people stupid, yes, but it doesn’t make them evil.

In [László Krasznahorkai’s] Satantango, the protagonist Irimias comments:

I don’t hold anybody personally responsible, but… I still want to ask you a question: aren’t we all equally guilty? Wouldn’t it be more honourable to admit our own responsibility instead of seeking comfort in cheap apologies? Because – and in this respect Mrs Halics is absolutely right – we cannot tell ourselves, simply to dampen the voice of our own conscience, that everything is just a curious coincidence, something that has nothing at all to do with us…

The dichotomy does not hold true. The critic can be on the artist’s side; Judas and Jesus can shake hands. A teacher, who has wronged someone, might be a good and important role model for someone else.

People cannot be divided into good and evil; both qualities exist within all of us, as a wise colleague once said.

And that, to my mind, is the essence of #metoo.

When Ville and Maaren’s case was investigated at the Sibelius Academy a few years after it had happened, many of the administrative staff were present, as was a lawyer. At the hearing, it was made unequivocally clear that such behaviour was wholly inappropriate for serving members of staff.

Maaren isn’t the only student with whom Ville has had interaction of a sexual nature, but according to Ville’s own account all of these cases took place before the hearing within the Sibelius Academy. There’s no reason not to believe this: none of the people I interviewed had heard of any recent cases involving him. On the contrary, many said they thought Ville seemed to have learned his lesson. Ville tells me that he has never had a sexual encounter with any of his own students.

The relationship with Maaren was a mistake, he says. In his words, what happened was the result of a crisis in his own life.

‘It resulted in behaviour that I can’t condone today and that I didn’t condone then either.’

I ask if he realised what kind of role model he was for Maaren.

In Maaren’s words: It’s important that teenagers have idols. The only difference is that you don’t bump into Leonardo di Caprio in the corridor at school. But you do bump into a musician you admire.

No, Ville didn’t realise that at the time. And I believe him: bad behaviour and transgressing boundaries is possible when you don’t realise how other people see you. It’s all too easy to ‘mess around’, as Ville describes his behaviour.

Still, what he did was wrong. He says he realised this while the relationship was still going on. Maaren wrote in her diary that Ville apologised for abusing his position of power.

Ville says he thinks it’s a good thing that people have started talking about this behaviour more than before, but says he is surprised that people constantly want to dig up his past again. The fact that the same story comes up again and again is frustrating for him. His employer has drawn a line under the matter, and he has visited a therapist too. He even spoke to Maaren a few years ago. (Maaren says that for a long time she blamed herself for what happened; after all, she had become involved with a married man. Only after the advent of the #metoo movement did she realise that this power relationship wasn’t equal.)

‘I get that attitudes have changed and now people are coming out all guns blazing,’ says Ville.

This isn’t about waging war, I reply.

So why must we return to this and many other cases, even after so long? Particularly if things aren’t black-and-white and we are all capable of making mistakes?

Perhaps it is for the same reason that our grandparents tell us about what happened during the war or what it felt like when their own parents administered corporal punishment. We address matters about which we have remained silent, either consciously or subconsciously. Paradoxically enough, I think it is only once we have admitted their existence that such things can stop existing.

A few more points.

Milla is so nervous that she still cannot perform without taking betablockers. When I tell her that, at a music camp in the early 2000s, I overheard one of the teachers praising her exceptional talent, she started to cry. If only someone had told me that back then, she said.

Riikka has graduated with a master’s degree in music but hasn’t played much for many years now. She can’t remember much about the time doing her master’s. She often panicked in concerts, felt utterly paralysed. It was as though she was watching herself from the outside. What am I doing here? To my teacher, I’m nothing but a wet dream, she thought. Riikka’s therapist believes that the trauma of Markku’s behaviour has caused her to develop symptoms of dissociative disorder.

It took Amalia years to get rid of the tensions that constant humiliation had sown in her body.

Years after the relationship ended, Maaren remembers asking whether Ville could take her on as a student. He said no. The reason he gave was the relationship. (Ville doesn’t remember this, but Maaren wrote about it in her diary.) She often wonders how her career might have been different if the relationship had never happened.

Anu remembers another example of harassment. At the end of January she sends me a voice message via WhatsApp: I remember one night when I was in a bar, underage, and all around me there were people from the orchestra, and suddenly a man in a very high position puts his hand on my thigh in such a way that I can’t do anything about it. Well, I guess we all know the feeling, that paralysing feeling that on the one hand it’s flattering, because he’s a really influential guy, but at the same time you realise you’re in a bar, you’re underage, you haven’t got any power, there’s nothing you can do. It’s a weird mix of utter bewilderment, flattery and disgust.

We return to things left behind us until someone or something makes it possible for even painful memories to change and become memories like any other. Then they evaporate, transform into shapeless images.

The music can finally be what it really is. I was wrong: Whiplash isn’t about music. It’s about a man who happens to be a musician and who, in the given circumstances, is capable of acting wrongly.

It was at an open discussion forum held at the Sibelius Academy a few years ago that Academy deacon Kaarlo Hildén realised there seems to be some confusion surrounding these matters. One of the teachers asked: what about relationships between staff and students? Are they allowed?

According to Hildén, they are categorically not allowed. If people fall in love, that is another matter, but a romantic relationship, in which a member of staff is put in a position of power over a student, will not be tolerated.

Hildén tells me that these matters are the subject of much internal discussion at the Sibelius Academy. In 2015 the University of the Arts published a guide to help prevent inappropriate behaviour. The guide explains concepts like bullying, sexual harassment and discrimination, and gives guidelines on how to stamp them out.

In the wake of #metoo, discussion has picked up. Many discussion panels and workshops have subsequently been held. In an email greeting, Hildén reminds all staff of the need for good behaviour: In a particularly shocking manner, the #metoo campaign has exposed the ways in which our society has routinely hushed up the matter of sexual harassment. Sadly this applies to the musical profession too. As an educational institution, it is our responsibility to create the best possible environment in which students can learn, flourish as artists, and forge a healthy professional identity. To that end, no form of harassment is ever appropriate, Hildén wrote to staff in spring 2018.

Yet there are still many unanswered questions that give pause. Many people have wondered why the Sibelius Academy payroll still includes people who have relatively recently been found guilty of sexual harassment. Have they been reprimanded or punished in any way? If so, how?

Some of this behaviour has been reported to the Sibelius Academy governors.

Hildén cannot comment on individual cases. Neither can he say how many times a member of staff can harass a student before being fired. Each situation is unique, he says.

I have only heard of one incident in which a relationship with a student led to a member of staff losing their job, and none of the people I interviewed had any information to the contrary. This particular case happened in the 1990s. Hildén says there is at least one other case, but he is not at liberty to give me any details.

It is also strange that Leif Segerstam recently oversaw an orchestra project with Sibelius Academy students. From the course feedback, we learn that Segerstam’s behaviour once again fell short of the standards one would expect. (Having said that, some of the feedback was very positive.)

‘There were many factors involved in the decision,’ says Hildén. He says that the student feedback has been ‘dealt with and taken very seriously’. Initially, the basis for the decision was Segerstam’s ‘extraordinary artistic expertise,’ Hildén explains.

But isn’t this precisely the problem, that other factors always supersede a person’s behaviour? Rather, shouldn’t we call time on this and say that, though we do not refute your musical abilities, repeated bad behaviour actually precludes you from leading a student orchestra project of this kind? As it stands, the decision seems to suggest that the way we treat other people is of secondary importance.

But there has been progress too, improvements in musicians’ judgement, in students’ understanding of their own rights, in general attitudes. At least, that’s what several people tell me. It would appear that there is greater awareness of these issues in the orchestral world too.

At the Sibelius Academy, the basic principles have been spelled out. Ethical Principles of the Teacher–Student Relationship at the Sibelius Academy, is the title of a PowerPoint presentation from 2019. The presentation was the result of collaboration between staff and students with the intention of continuing the discussion.

The relationship between teacher and student is professional in nature and is intended to foster study; sexual relations of any kind or speech or physical contact of a sexual nature have no place at all in such a relationship, and neither does commenting upon another’s appearance.

Due to the nature of the power relationship, the teacher’s responsibility for creating a functioning teacher–student relationship is greater than that of the student. This involves, e.g. an awareness of that power relationship and of its existence beyond standard teaching situations. The teacher, therefore, has a greater responsibility for interaction, for making these different roles and situations apparent and, where necessary, verbalising them for others. It is the teacher’s responsibility to create a safe learning environment for all students.

On paper, it seems, everything is clear.

A musician friend and I talk about shame. It’s an emotion with which we are both familiar. For instance, my friend often feels ashamed at not being able to do something related to a given playing technique.

‘There are lots of pieces I don’t ever want to play, because I’ve got such a strong sense that I can’t play them.’

‘Me too. I guess that’s why I stopped playing altogether.’

Over the years, many people have wondered why I didn’t apply for professional studies at the Sibelius Academy; they’ve even asked me while I was preparing this article.

There’s no simple answer. But I remember my own thought process: I cannot get up in front of an audition panel ever again. I applied to the Sibelius Academy youth department three times, and by the time I finally got in, I hated my own playing more than ever before. The sense of disgust didn’t come from any one specific place, and it certainly had nothing to do with my teachers. But the atmosphere at the Sibelius Academy was such that I simply couldn’t handle it.

Though almost fifteen years has passed, I can still recall the shame associated with performing. To this day, I still don’t play ‘for my own enjoyment’. I don’t feel any sense of joy at what my playing sounds like; I’m not sure I ever did.

Shame prevents us from being free. I wonder whether this could be one reason why the question of equality in the music world seems to move so agonisingly slowly. When the matters at hand are complicated and when so many people feel ashamed about their behaviour, both to others and themselves, it’s hard to have an open discussion.

The New Yorker recently ran an article by Joshua Rothman entitled ‘The Equality Conundrum’. Rothman quotes Hannah Arendt’s assertion that the Holocaust reveals there is nothing inherently sacred about humanity. “If that’s true,” he writes, “then equality may be not a self-evident fact about human beings but a human-made social construction that we must choose to put into practice”.

Putting it into practice feels difficult, because that’s what everything feels like at first. But if you decide to achieve something, you have to force yourself into the practice room, you have to pick up your tools, your instrument, and start practicing. You have to think the way a friend of mine thinks about contemporary music, music she never played as a student and which for that reason isn’t associated with the same sense of shame and trauma:

‘If you never question the learning process or yourself, you can learn things by force if necessary. I think to myself, fuck it, I have to learn this.’ This, despite the fact that what we do can sometimes feel bad and inadequate. Nowadays my friend thinks recognising your own shortcomings is the foundation of all learning. One cannot exist without the other.

As with playing, equality too is about understanding that our ideals are much higher than the levels we can achieve. That doesn’t mean, however, that we shouldn’t strive towards something better. Without the dream of achieving the impossible, classical music wouldn’t exist either.

The names of people appearing in this article have been changed due to the delicate nature of the subject. Quotations have been adapted as necessary to maintain the anonymity of all interviewees. Jan Söderblom, concertmaster of the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, was also interviewed in the preparation of this article. A longer interview with Sibelius Academy deacon Kaarlo Hildén can be read at apu.fi/image.

English translation: David Hackston – The original article was published in Finnish on March 7th 2020.